The death of dying

Life is getting longer.

Life expectancy in Australia grew from 50 years in the late 1800s, to 70 in the 1960s, to 82 or so today. And we’re nowhere near finished. But while many are aware of this, not many appreciate the magnitude of this achievement, nor its continuous impacts.

Perhaps there’s a lack of newspaper headline moments claiming “1,000 people did not die yesterday”. Or perhaps it’s because people think lives are merely being elongated when we’re at our worst, forcing us into a dependent cycle of medical attention from which the doctors gain more than the patients.

Yet, neither of these is entirely true.

Making headlines every day

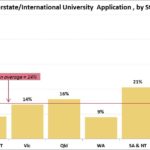

While 154,000 Australians died in 2014 (latest data available), the figure would have been closer to 176,000 (22,000 more deaths) had the mortality rate not improved in the last 10 years. (And 10 years is hardly a long time. In today’s currency, it’s barely 5 Prime Minsters ago.) Improvements since 2004 are saving an extra 2,200 people each year, on average. To put it in perspective, around 230 people are murdered in Australia each year. So mortality improvements, which rarely rate a mention, are saving 10 times the number murdered more every year than the last!

Seeing as murders are front page material, mortality improvements should have their own weekend section.

Saving lives at all stages

Unlike popular opinion, extending life expectancy is not about delaying death while holding people to ransom, feeding them mashed cauliflower through transparent tubes. Death rates for teenagers and kids under 5 year-olds have both decreased by a third. Basically, we’ve saved 1 in 3 of the teenagers (and babies) who would have died had the improvements not occurred.

Had we saved a third of the price of electricity Josh Frydenberg would have declared it a national holiday.

These decreases were not a once off, nor were they specific to one group. Improvements across the younger years have been pretty steady over the past decade.

Improvements in mortality rates translate into less people dying than would have under the previous rates.

As expected, the majority the decrease in deaths occurs at the latter stages of life. Though surprisingly, the only cohort with an increasing mortality rate are those over 95 years of age. And yet, the improvements are so large that even though the younger cohorts make up smaller percentages, they are still newsworthy. Without the improvements of the last 10 years, 2014 would have seen the death of around:

- 376 more kids under 5

- 124 more teenagers

- 426 more people in their 20s

- around 3000 more working aged folk (15-65 year-olds)

Instead, our attention is focused on gruesome anecdotes of villains and victims. A hero cowardly king-hit, a young family destroyed by a murder-suicide, three teenagers overdosing on ice behind the local servo, or a joy ride gone awfully wrong. Without balancing these out with the constant excitement of decreasing mortality and longer lives, we fall into a pessimistic spiral of despair. We fail to recognise the huge progress made and foster a sense of nostalgia for times which were in fact significantly worse.

Shit’s never been this good. We’re just too busy reading the headlines to realise it.

Source:

Death figures sourced from : ABS Deaths Publication, 2014 http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/3302.0

Converted to rates using ERP by age