There is no doubt that Australian property prices are increasing at a rapid rate. Affordability, however, may depend on expectations.

There is a difference between something being unaffordable and it rapidly increasing in price. The topic of housing affordability has been on high rotation in Australian politics for the past few years. It’s the pinnacle of two topics du jour: Capital Gains Tax and Negative gearing. Much has been written about the impact these two policies have had on house-prices since the 1980s. However, most articles focus on the speed of the price increase, not on whether houses are relatively ‘affordable’? What is affordable? Would we think houses affordable if prices dropped by a third?

Much was made of Turnbull’s interview with the one-year-old who negatively geared property (or at least her parents did), and how out of touch the sentiments of the interview were. But it is generally acceptable, on the other hand, for a couple with a 4-month-old to own a home with spare rooms¹.

“We don’t have unreasonable expectations, but those three-bedroom apartments and townhouses are cost prohibitive ….” said Ms Rule-Layton, Coburg.

Census figures show that when it comes to young families with one or two children, spare bedroom(s) are by far the norm, not the exception.

Of the 207,000 couples with one child owning (or paying off) a home in 2011, 91% had at least one spare room. Almost half of these had 2 spare bedrooms or more.

The situation is surprisingly similar for single parents with one kid. More than 4 out of 5 had at least one spare bedroom, and 27% at least 2.

When it comes to 2 children families, the question of spare bedrooms is slightly more complicated as the issue of sharing bedrooms arises. Statistics usually show you how many people and rooms there are per home, but not whether kids share rooms making others spare, etc. However, only 3 in 100 home-owning couples with 2 kids had insufficient rooms for their kids not to have one each. This figure only rises to 5 in 100 for single parents with 2 kids.

According to the Real Estate Institute of Victoria, 3bdr apartments and houses in inner Melbourne are on average 54% and 32% more expensive than the 2bdr variety. That roughly equates to an extra $310k for the 3rd bedroom of an apartment, and $285k in a house.

This ratio may not be representative of the whole country but it does suggest that the 3rd bedroom contributes substantially to the price of the dwelling (approximately 30% across the greater Melbourne).

Would homes be deemed affordable today, if the price dropped by this amount?

If families were willing to live without the luxury of a spare bedroom, this saving becomes a real possibility. This relates to the 9 out of 10 couples with one child, and 55 out of 100 couples with 2 children. Also, to the 42 in 100 families with two kids who have individual rooms.

However, it seems Australians fear room sharing more than they do debt.

The extra bedroom phenomenon is not limited to Australia’s elite. The ratio of houses with at least one spare room is remarkably similar across all socio-economic backgrounds for couples and single-parent families with one child. The difference becomes noticeable on households with 2 or more spare bedrooms.

And while the spare bedroom, beyond individual kids’ rooms becomes more difficult for the less well-off families, only 9% of the poorest single-parent families don’t have enough rooms for their kids to sleep separately.

There is no doubt that Australian property prices are increasing at a rapid rate. Affordability, however, may depend on expectations.

Australia’s housing standards are amongst the highest in the world. The OECD ranks Australia’s housing at 4t4h highest out of the 36 compared in the Better Life Index². Furthermore, within this champagne crowd Australia’s housing costs come a timid 11th cheapest (of the 36) in terms of housing costs vs disposable household income.

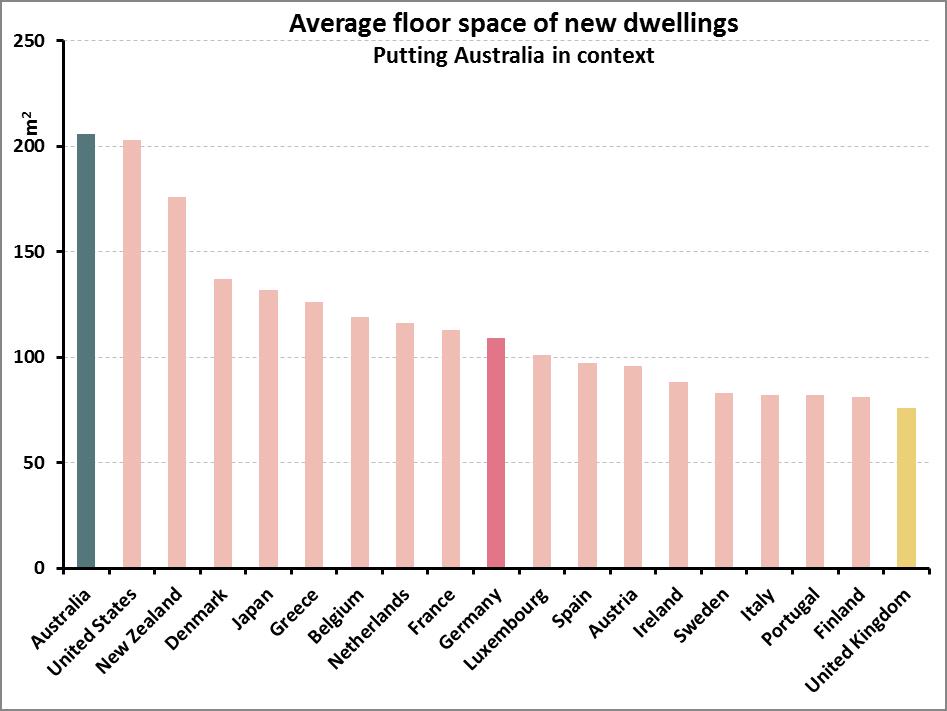

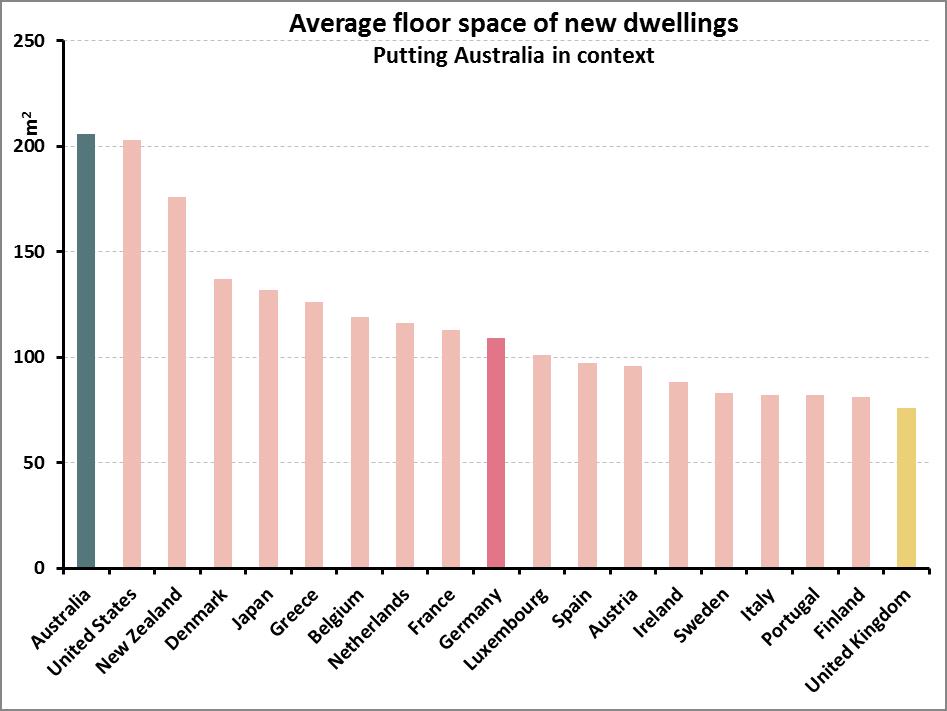

Not only are Australian housing standards particularly high, but they are also improving fast. The average floor-space of new homes increased by almost 40% since 1985³, to 208 metres2 in 2013. To put this in context, the average new home in Germany is 109m2 and in the UK it is 76m2.

Based on the best international comparisons I could find4, Australia leads the way in size of new dwellings, easily doubling the size of many European countries’.

So, when we hear international house price comparisons, it’s worth remembering we’re not always comparing apples with apples, but rather their apples with our watermelons.

Does Australia have a housing affordability crisis? It’s hard to say. It depends on your definition of affordable. However, there is a lot of room to move if we want to decrease the cost of housing without lowering our standards beyond what is considered acceptable across the rest of the world’s richest countries.

After all, do we even want our in-laws to have a spare room at our place to crash in? Save yourself the $300k, and shout them a five-star hotel for the few nights a year they do visit the grandkids.

[1] http://www.domain.com.au/news/melbourne-apartment-boom-is-it-working-for-buyers-and-residents-20160429-gogjvs/

[2] http://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/topics/housing/

[3] http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Previousproducts/8752.0Feature%20Article1Jun%202013

[4] http://www.demographia.com/db-intlhouse.htm

The report’s major strength is that it compares a finer slice of the community, focusing on schools with similar socio-economic backgrounds. This removes the effect of funding allocations based on need, which the government currently follows. Seeing as public schools disproportionately service poorer areas, using PC’s rough average (as I did) overestimates the difference in funding as the population serviced by private schools is generally cheaper to support. Unfortunately, the complete MySchool data is not easily available online, so my analysis is restricted to aggregate data and misses this finer level investigation.

The report’s major strength is that it compares a finer slice of the community, focusing on schools with similar socio-economic backgrounds. This removes the effect of funding allocations based on need, which the government currently follows. Seeing as public schools disproportionately service poorer areas, using PC’s rough average (as I did) overestimates the difference in funding as the population serviced by private schools is generally cheaper to support. Unfortunately, the complete MySchool data is not easily available online, so my analysis is restricted to aggregate data and misses this finer level investigation.